Introduction

Welcome to FYZICAL Brodie Lane's resource on concussions.

A concussion is a brain injury caused by acceleration or deceleration of the brain following a significant impact to the head or elsewhere on the body. The impact causes dysfunction within brain cells and decreased blood flow, resulting in temporary deficits in brain function. Symptoms may include loss of consciousness, headache, pressure in the head, neck pain, nausea or vomiting, cognitive problems, dizziness, or balance problems, among others.

This guide will help you understand:

- how the condition develops

- how health care professionals diagnose the condition

- what treatment approaches are available

- what FYZICAL Brodie Lane’s approach to rehabilitation is

Anatomy

What is the anatomy of the brain?

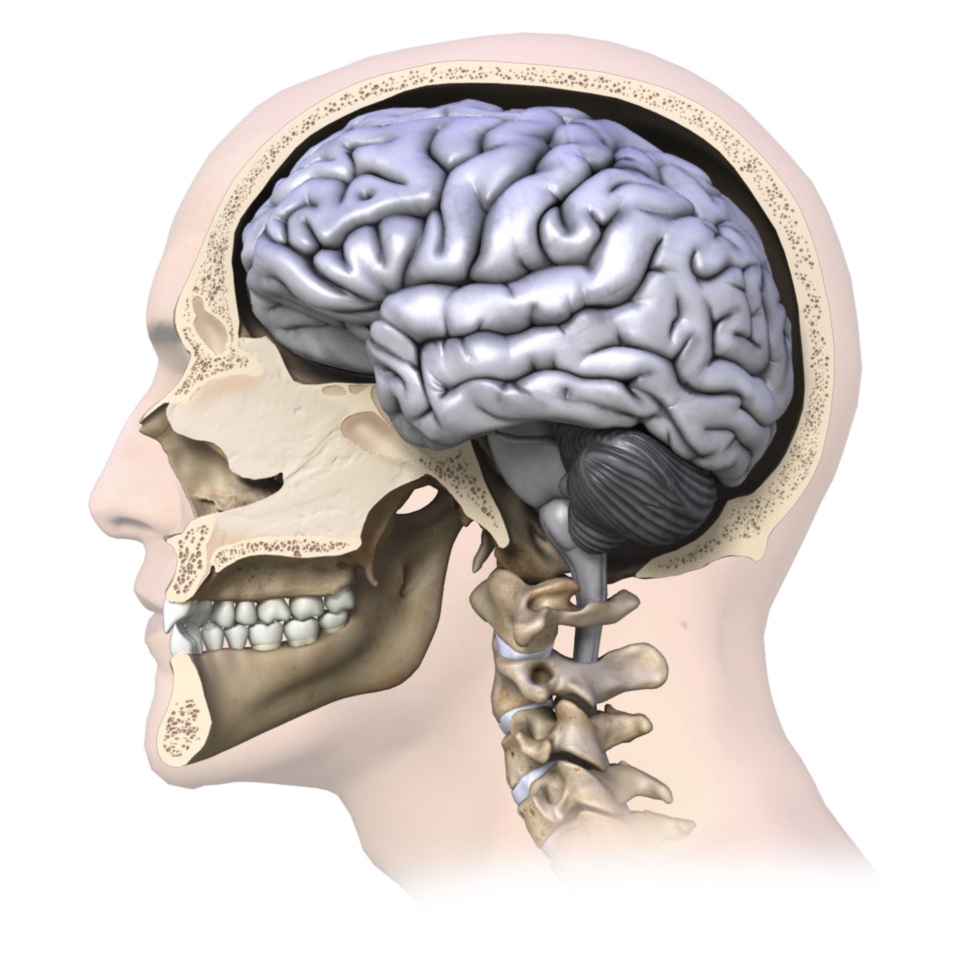

The brain is a soft organ that sits in the hard skull for protection. It is cushioned by cerebrospinal fluid that fills in the space between the skull and the brain. The cerebrospinal fluid acts like packing foam that protects your fragile items from both the sides of the hard moving box itself and from the rapid or sudden motions that the box may endure.

The brain is the control centre for all of the body’s activities. Damaging the brain can alter your ability to perform tasks both mentally and physically.

Causes

What causes a concussion?

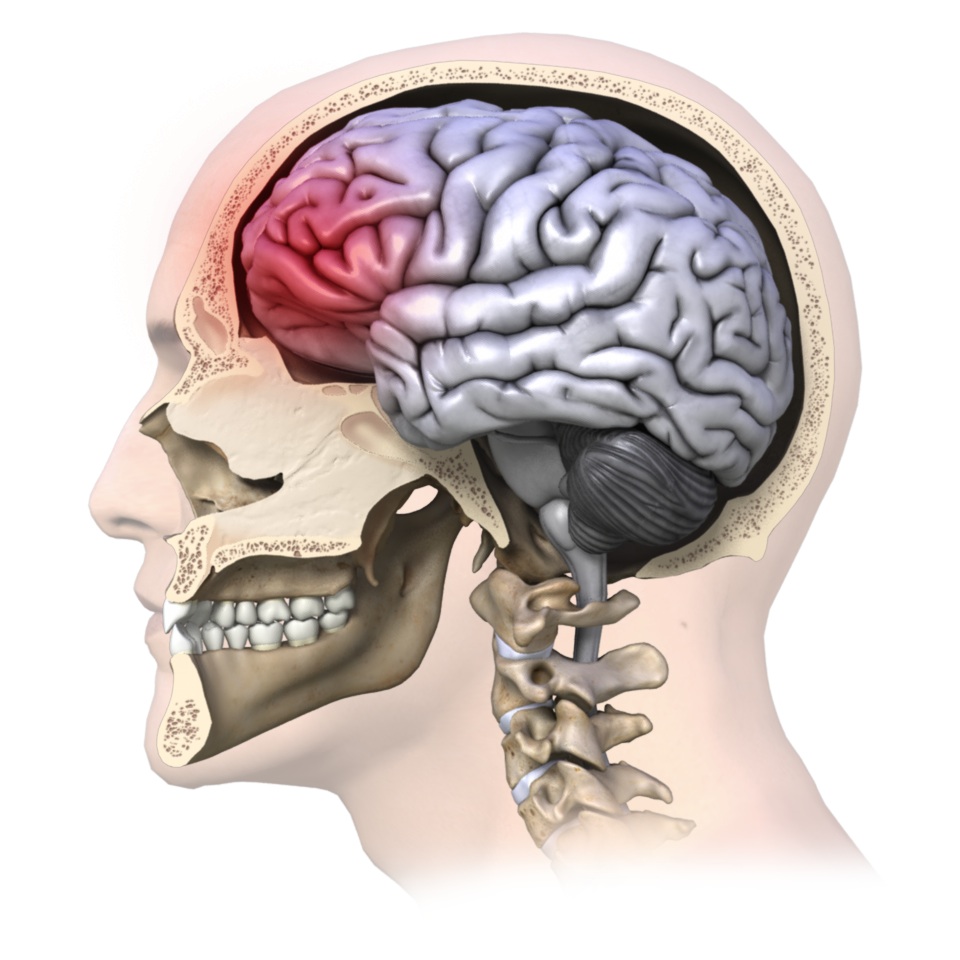

Any forc e that causes the brain to move rapidly within the skull and bang against the inside of the skull can cause a concussion. In layman’s terms, a concussion can be caused by anything that ‘rattles the brain.’

e that causes the brain to move rapidly within the skull and bang against the inside of the skull can cause a concussion. In layman’s terms, a concussion can be caused by anything that ‘rattles the brain.’

Typically concussions are thought to be caused by direct blows to the head, such as in boxing or bar fighting, or by hitting your head on the ground during a fall, but indirect forces to the head are also common causes of concussions. For example, a fall onto your buttocks or onto any other part of your body can transmit a force strong enough to your brain to cause a concussion, even if you do not hit your head during the fall. Similarly, a blow to your neck, face or any other area of your body that is severe enough to transmit the force to your head can cause a concussion.

Motor vehicle accide nts often similarly cause concussions due to the whiplash motion of your neck which subsequently forces your brain to rapidly hit the inside of your skull. Shaken baby syndrome is another example of this indirect mechanism of brain injury, as are explosions where your body is rapidly thrown back.

nts often similarly cause concussions due to the whiplash motion of your neck which subsequently forces your brain to rapidly hit the inside of your skull. Shaken baby syndrome is another example of this indirect mechanism of brain injury, as are explosions where your body is rapidly thrown back.

Symptoms

What are the symptoms of a concussion?

Signs and symptoms of a concussion can vary extremely between people. It is not always obvious that someone has a concussion, so if the mechanism of injury for a concussion was present, a concussion should always be suspected and thoroughly investigated.

You do not need to lose consciousness to suffer a concussion, and in most cases there is no loss of consciousness. If you do lose consciousness, however, you have most certainly sustained a concussion. Any loss of consciousness should be taken seriously, and any bouts lasting more than approximately a minute are considered severe.

Signs and symptoms of a concussion can vary extremely between individuals and can last days, weeks, months, or even longer in some cases. Fortunately, however, in the majority of cases symptoms usually resolve within 7-10 days.

One of the most common symptoms of a concussion is a headache. Con fusion is another common sign. This sign can easily be overlooked by the examiner unless the patient is moderately to severely confused, so ruling out a concussion should not be based on the fact that the patient ‘did not appear confused.’

fusion is another common sign. This sign can easily be overlooked by the examiner unless the patient is moderately to severely confused, so ruling out a concussion should not be based on the fact that the patient ‘did not appear confused.’

Other signs and symptoms of a concussion that may be present on their own or in combination are concentration difficulties, decreased attention, difficulty with mental tasks, memory problems, difficulties with judgment, a decrease in balance and coordination, a feeling of disorientation, a feeling of being ‘dazed,’ fatigue, blurred vision, light and/or sound sensitivity, difficulty sleeping or sleeping more than usual, being overly emotional, being irritable or sad, neck pain, a feeling of ‘not being right’, and ringing in the ears. Amnesia may be another symptom. Two types of amnesia can occur: Retrograde amnesia which is forgetting events that happened before or during the concussion event, or anterograde amnesia, which is when you do not form new memories about events that occurred after the concussion. In severe concussions, a change in personality may even occur. If a patient shows even one sign or symptom listed above this should be indicative of a concussion occurring and a full concussion evaluation should proceed.

Signs and symptoms that are even more severe after an injury to the head, such as recurrent vomiting, a change in pupil size, blood or fluid coming from the ears or nose, seizures, or obvious physical coordination or mental difficulties indicate a severe brain injury and require immediate emergency attention.

In most cases signs and symptoms appear immediately after the concussion has occurred, however in some cases the signs and symptoms can be delayed by a few hours or possibly even days. For this reason if the mechanism of injury suggests a concussion despite a lack of obvious symptoms being immediately present, the patient needs to be thoroughly examined for latent development of concussion signs or symptoms over a reasonable time frame, and a concussion must be thoroughly ruled out before returning to activity.

Diagnosis

How do health care professionals diagnose a concussion?

Diagnosing a concussion can be easy in cases where there was an obvious mechanism of injury involving a blow to the head, and when there are immediate signs and symptoms to indicate the brain has suffered an injury.

In many cases, however, a concussion can be overlooked when the mechanism of injury does not directly involve a blow to the head, the signs and symptoms are not obvious, or the signs and symptoms are delayed in their onset. The patient may initially ‘appear fine.’

Diagnosis of a concussion begins with a complete history of the mechanism of injury. As stated above, any blow to the head or force through the body that is strong enough to transmit a force to the head will lead your health care professional to the suspicion of a concussion. At a sporting event, often the sideline health care professional is privy to having seen the mechanism of injury, which aids in diagnosing a concussion. Included in the history will be questions regarding any previous concussions that the patient may have incurred. The more concussions you incur, the higher your chances of sustaining another concussion, and it can more easily occur with decreased force.

Thorough questioning regarding the patient’s symptoms is the next step to diagnosing a concussion. With sporting events, immediate symptom evaluation should occur on the sidelines by a health care professional or a coach well educated in concussion signs and symptoms. If neither is available, immediate referral to a doctor should occur.

As symptoms can appear immediately or can be delayed, monitoring of symptoms from the time of concussion for at least a few hours is necessary. As mentioned above, symptoms may even be delayed a few days so if the mechanism of injury indicates a potential for a concussion, the development of symptoms needs to be monitored for a few days after the injury, and during this time, the patient should not be allowed to participate in sport or challenging cognitive activities. It is important to monitor for not only the initial emergence of any concussion signs or symptoms, but also for the worsening of any existing symptoms, or any decline at all in the patient’s ability to perform physical or cognitive tasks.

The evaluation of cognitive function should occur when initially diagnosing a concussion. General questions regarding orientation that have traditionally been used such as ‘who are you?’, ‘where are you?’, and ‘what time is it?’, have not been shown to be sensitive enough to pick up a decline in cognitive function. For this reason diagnosis of a concussion should not be ruled in or out based solely on these general questions. More advanced questioning can be useful in helping to determine a decline in cognitive function indicating injury to the brain. For instance, at a sporting event questions such as ‘who scored the last goal?’, ‘which team was played last week?’, or ‘how far into the game is it?’ can help to delineate a concussive state. More advanced sideline concussive cognitive tests are also available and are useful in sports where concussions are common. Outside of sport, more in-depth questioning such as the exact location of a street, or questions regarding the full date and time of day may assist in determining the patient’s cognitive status.

Whether on field, at the emergency department, or in the medical clinic a thorough physical examination will need to be completed. This examination is to look for signs such as pain in the neck, which may indicate a concurrent cervical spine injury, amnesia, or soft tissue injury to the skull.

Following the physical examination a clinical neurological examination is completed including tests for strength and sensation, reflexes, coordination, visual and auditory disturbances, and cognitive impairment including deficits to memory or concentration. A thorough examination of the patient’s balance and gait will also be completed. Impairment in balance can often be seen as a clinical sign of reduced motor function when a patient suffers a concussion. Balance that is not disturbed, however, does not exclude the diagnosis of a concussion having occurred.

A concussion is a functional injury to the brain rather than a structural injury. This means that damage to the brain tissue generally cannot be physically seen. For this reason, neuroimaging tests such as computerized tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance images (MRI) that look at brain structure are not needed to diagnose a concussion. Normal findings are common when imaging is completed in patients who show clinical signs of a concussion. In other words, you can still have a concussion, even a severe one, despite CT scans or MRI results being normal. For this reason, neuroimaging is not routinely ordered if a concussion is diagnosed, unless true structural damage to the brain is suspected. X-rays of the skull may be considered to rule out bony injury to the skull itself if the mechanism of injury warrants it.

If structural damage to the brain is suspected a CT scan or MRI is necessary as these are currently the best neuroimages readily available to view the structure of the brain. Structural damage may be suspected when concussion signs or symptoms are severe. For example if there has been a significant loss of consciousness (greater than one minute), significant memory loss, a change in pupil size, repetitive vomiting, seizures, or rapidly worsening levels of cognition or physical ability. Even if the concussion symptoms are not severe, but the mechanism of injury involved enough obvious force to cause structural damage then a neuroimage of the brain is indicated. For example, concussions due to falling from a height or from a high-speed motor vehicle accident would warrant a neuroimaging test. Neuroimages may also be more routinely ordered in adolescents or children due to the fragility of their developing brains.

Currently there are no neuroimaging tests used routinely that can identify the changes in the brain that relate directly to the clinical signs and symptoms seen with a concussion. New MRI neuroimaging testing which is sensitive to brain electrical activity (functional MRIs also knows as fMRI) and MRIs that are more sensitive to minute structural damage (perfusion and diffusion tensor imaging), as well as other types of new imaging technologies are currently being trialed and extensively researched. These tests show hope in potentially creating a gold standard neuroimage test that identifies a concussive state. Some major hospitals or clinics may already have these tests available, and if so, these tests add valuable information to diagnosing a concussion and analyzing clinical symptoms. At this stage, however, not enough research has been completed on these tests to warrant their use as a standard procedure in the diagnosis of a concussion.

Medication

Can medications help me after a concussion?

Immediately after sustaining a concussion medications should be avoided until a full assessment of the concussion signs and symptoms can be reviewed. Even over-the-counter drugs such as ibuprofen, nurofen, paracetamol, or acetaminophen should not be taken after a concussion until a doctor is consulted.

Once reviewed by a doctor, if medication is prescribed its aim is for one of two reasons: Firstly, medication may be prescribed to treat the concussion injury itself in an attempt to decrease initial symptoms or duration of symptoms. Secondly, medication may be used to deal with the symptoms arising from the concussion such as sleep deprivation, or emotional lability. Many doctors choose not to medicate at all when treating a concussion in order to not mask any symptoms. If medication is prescribed the doctor who prescribes it should closely monitor the patient and all health care professionals involved in the patient’s care should be aware of how the medication may affect the symptoms of the concussion.

Alcohol and illicit drugs should be strictly avoided when recovering from a concussion.

Treatment

What is the treatment for a concussion?

The basis of treatment for all concussions is rest until signs and symptoms resolve. Once signs and symptoms have resolved then a graduated increase in both cognitive and physical activity is implemented while monitoring symptoms. Once graduated activity is implemented and tolerated then a graduated return to sport or work schedule can be considered. Rest for a concussion means both a physical rest but also a cognitive rest. This means not only will sporting activities or manual work activities be excluded, but also mental activities requiring attention and concentration such as television watching, computer work, reading, texting, or doing schoolwork. The brain simply needs time to heal, as with any other injury to the body. The eyes and ears can be particularly sensitive to sound and light after a concussion and even normal lights and sound can precipitate symptoms so any stimulus of this sort needs to be avoided or limited.

If a concussion is suspected during a sporting event the player should be immediately removed from the game and not be allowed to return to play that day under any circumstance. Serious injury to the cervical spine should be ruled out and then a full concussion examination should proceed. An ice pack can be applied to the neck or head if pain is present in either of these areas. If it is unclear whether a concussion may be present, it is recommended to err on the side of caution and assume a concussion is present until thoroughly ruled out. The common sporting cliché of “when in doubt, sit them out” should be applied. In the event of an injury occurring outside of sport that involves significant impact or force, such as a motor vehicle accident or fall from a height, one should assume that a concussion has occurred until this has been thoroughly ruled out.

Immediately after a concussion a patient should not be left alone and should be monitored for any development of new signs and symptoms or any deterioration in existing signs and symptoms over a period of a few hours. If the patient does not exhibit any signs or symptoms indicating a severe concussion and they have not deteriorated over several hours of monitoring them, it is fine to let them sleep, as this will aid their recovery. They do not need to be awoken every few hours unless a doctor has examined them and has specifically suggested that this be done. In severe cases, some concussed patients may be kept in the hospital for monitoring overnight.

Fortunately the majority of concussions (80-90%) resolve in a short period of 7-10 days. Several factors, however, may lengthen recovery times and will require typical management of a concussion to be modified. Severe concussions or those concussions where the symptoms last longer than expected will require a longer recovery period. Patients who have had a loss of consciousness of greater than one minute also generally require a longer recovery period, as do children and adolescents whose brains are still developing and are therefore more sensitive to injury. Repetitive concussions create cumulative injury to the brain and therefore generally require a longer period to recover after each time they occur. There is also a thought that females may incur more severe concussions due to their lesser neck musculature compared to males. The increased male musculature may help to absorb some of the forces that the body (including the brain) endure which may decrease the severity of a concussion. For this reason females may require a longer recovery period before returning to work or play. Interestingly, patients who suffer from migraines, mental disorders, depression, sleep disorders or attention deficit syndrome may also require a longer period to recover and these factors should be considered when planning return to activity protocols.

Conclusion

The brain is a delicate, sensitive, and complex organ. Injury to the brain has the potential to affect aspects of both physical and cognitive functioning in activities of daily living as well as during activities of sport and work. Most signs and symptoms of a concussion resolve relatively quickly, but in some cases signs and symptoms can last longer than anticipated and continue to affect a patient’s ability to function.

The best treatment for concussion is prevention. When a concussion does occur, however, the seriousness of the event needs to be acknowledged by the patient, the health care professional, and any other caregiver involved. A comprehensive and cautious approach to treatment, recovery, and return-to-activity must be implemented.