Introduction

Physical therapy in Venice for Knee

Welcome to FYZICAL Venice's patient resource about Articular Cartilage Problems of the Knee.

Articular cartilage problems in the knee joint are common. Injured areas, called lesions, often show up as tears or pot holes in the surface of the cartilage. If a tear goes all the way through the cartilage, surgeons call it a full-thickness lesion. When this happens, surgery is usually recommended. However, these operations are challenging. Repair and rehabilitation are difficult. Your surgeon will consider many factors when determining the procedure that's best for you.

This guide will help you understand:

- what your surgeon hopes to achieve

- what happens during the procedure

- what to expect after surgery

Anatomy

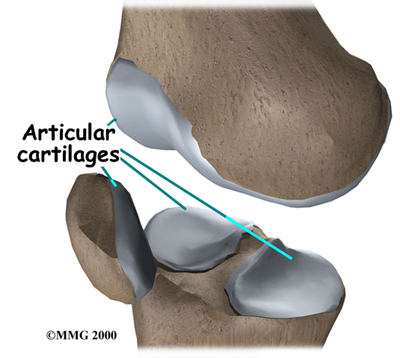

Where is the articular cartilage, and what does it do?

Articular cartilage covers the ends of bones. It has a smooth, slippery surface, which allows the bones of the knee joint to slide over each other without rubbing. This slick surface is designed to minimize pressure and friction as you move.

When the surface of the cartilage is injured, it is usually not painful at first. This is because cartilage tissues are not supplied with nerves. However, any holes or rough spots in the cartilage can throw off the intricate design of the joint. If this happens, the joint can become inflamed and painful. If the injury, or lesion, is large enough, the bone below the cartilage loses protection, and pressure and strain on this unprotected portion of the bone can also become a source of pain. Finally, if the cartilage injury isn't treated, it may eventually cause other problems in the joint.

Surgeons classify defects in the knee cartilage using a grading scale from I (one) to IV (four). In a grade I tear, the cartilage has a soft spot. Grade II lesions show minor tears in the surface of the cartilage. Grade III lesions have deep crevices. In grade IV lesions, the tear goes all the way to the underlying bone.

The following images show each type of defect

Grade I

Grade II

Grade III

Grade IV

A grade IV lesion goes completely through all layers of the cartilage. It is diagnosed as a full-thickness lesion. Sometimes part of the torn cartilage will break off inside the joint. Since it is no longer attached to the bone, it can begin to move around within the joint, causing even more damage to the surface of the cartilage. Some doctors refer to this unattached piece as a loose body.

Grade IV - All Layers

Cartilage lacks a supply of blood or lymph vessels, which normally nourish other parts of the body. Without a direct supply of nourishment, cartilage is not able to heal itself if it gets injured. If the cartilage is torn all the way down to the bone, however, the blood supply from inside the bone is sometimes enough to start some healing inside the lesion. In cases like this, the body will form a scar in the area using a special type of cartilage called fibrocartilage. Fibrocartilage is a tough, dense, fibrous material that helps fill in the torn part of the cartilage. Yet it's not an ideal replacement for the smooth, glassy articular cartilage that normally covers the surface of the knee joint.

Related Document: FYZICAL Venice's Guide to Knee Anatomy

Rationale

What does the surgeon hope to accomplish?

Articular cartilage lesions do not always cause symptoms. In fact, surgeons many times happen upon lesions in the knee joint cartilage while doing knee surgery for a completely different problem. Just because there isn't any pain does not mean the lesion is not causing problems. In general, partially torn lesions do not heal by themselves. And they often get worse over time, not better.

Likewise, full-thickness lesions may not cause any symptoms at first. The fibrocartilage that fills in the injured space often doesn't match the shape of the joint surface. The body may have problems adapting to the altered shape of the joint, which can eventually even change the way the joint works.

When the lesion causes pain, surgery will most likely be recommended. If the lesion is not causing symptoms, there is less certainty about what to do. Will surgery help? Or could it make the situation worse? In these cases, surgeons will weigh many factors before recommending surgery, such as the patient's age and lifestyle, the overall condition of the knee, and how bad the lesion actually is.

Even if patients have pain, they may not have surgery right away. Doctors may start by recommending ways to manage the symptoms. This could be as simple as applying heat or ice and taking prescription medication. Often, doctors will recommend patients work with a physical therapist. A knee brace or shoe orthotic may be issued to improve knee alignment to ease pressure on the sore knee.

Preparation

What should I expect before surgery?

Before surgery, your surgeon will need to find out as much as possible about your knee. In addition to your physical exam, you will need more X-rays and possibly other imaging tests, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and bone scans. Your surgeon may also need to use an arthroscope (discussed later) to check the lesion's location, size, and depth.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during surgery?

Many types of surgery have been developed for fixing articular cartilage injuries in the knee. When the decision is made to go ahead with surgery, the surgeon will consider whether to do a procedure to restore or to repair the cartilage. A reparative surgery can help fill in the lesion, but it doesn't completely restore the actual makeup and function of the original cartilage. (Sometimes that simply isn't possible given the amount of damage in the knee.) Reparative procedures may provide pain relief and improve knee motion and function.

Your surgeon would ideally like to help your knee return to its natural state, with full function and no pain. This requires restorative surgery, meaning that the end result is a lesion filled to the full depth by tissue identical to the original. Surgeons rely on some fairly new procedures to substitute or replace the original cartilage. One method is to transplant cartilage and underlying bone from a nearby area in the knee joint. Another method is to take some chondrocytes (the primary cells of cartilage) from your knee cartilage, grow them in a laboratory, and then use the newly grown tissue to fill in the lesion at a later date.

The final decision about which surgery to use will be based on your specific injury, age, activity level, and the overall condition of your knee.

After Surgery

What happens after surgery?

After surgery, patients go to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) for specialized care until they awaken. Then they are either transferred to the nursing unit or released from the hospital. Many of the procedures for treating articular cartilage are done on an outpatient basis, meaning you can leave the hospital the same day.

Since surgeons use different methods when treating articular cartilage lesions in the knee, the instructions patients need to follow after surgery depend on the surgeon and the way the surgery was done.

Portions of this document copyright MMG, LLC.

Our Rehabilitation

What should I expect during my recovery?

When you begin your physical therapy at FYZICAL Venice, our first few physical therapy treatments are designed to help control the pain and swelling from the surgery. We will also work with you to make sure you only put a safe amount of weight on the affected leg.

With the exception of those who undergo a simple debridement, our patients will be instructed to avoid putting too much weight on their foot when standing or walking for up to six weeks. This gives the area time to heal. Our patients treated with an allograft are often restricted in their weight bearing for up to four months.

We strongly advise you to follow our recommendations about how much weight is safe. You may require a walker or pair of crutches for up to six weeks to avoid putting too much pressure on the joint when you are up and about.

Depending on the type of surgery, our physical therapist may have you use a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine to help your knee begin to move and to alleviate joint stiffness. This machine is used after many different types of surgery involving joints and is usually started immediately after surgery. The machine straps to the leg and continuously bends and straightens the joint. This continuous motion has been shown to reduce stiffness, reduce pain, and help the joint surface heal better with less scarring.

Your physical therapist will choose exercises to help improve knee motion and to get your muscles toned and active again. At first, we will place emphasis on exercising the knee in positions and movements that don't strain the healing part of the cartilage. As your program evolves, we will choose more challenging exercises to safely advance the knee's strength and function.

Ideally, patients will be able to resume their previous lifestyle activities. Some patients may be encouraged to modify their activity choices, especially if an allograft procedure was used.

At FYZICAL Venice, our goal is to help you keep your pain under control, ensure safe weight bearing, and improve your strength and range of motion. When your recovery is well under way, regular visits to our office will end. Although we will continue to be a resource, you will be in charge of doing your exercises as part of an ongoing home program.

FYZICAL Venice provides services for physical therapy in Venice.

Portions of this document copyright MMG, LLC.