Introduction

Physical therapy in Hazle Township for Shoulder Issues

Welcome to FYZICAL Hazleton's resource about shoulder dislocations.

Welcome to FYZICAL Hazleton's resource about shoulder dislocations.

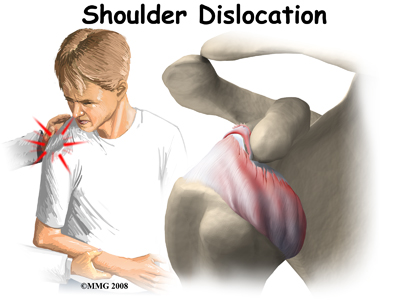

A shoulder dislocation is a painful and disabling injury of the glenohumeral joint. Most dislocations are anterior (forward) but the shoulder can also dislocate posteriorly (backwards). Inferior and posterolateral dislocations are possible but occur much less often. The specific type of dislocation is based on the position of the humeral head in relation to the glenoid (shoulder socket) at the time of the diagnosis.

This guide will help you understand:

- what parts of the shoulder are involved

- how the problem develops

- how health care professionals diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

- what FYZICAL Hazleton’s approach to rehabilitation is

Anatomy

What parts of the body are involved?

The shoulder has a unique and complex anatomy that allows range of motion and coordination needed for reaching, lifting, throwing, and many other movements. Understanding the anatomical structures discussed will help you understand why your shoulder dislocated.

The shoulder has a unique and complex anatomy that allows range of motion and coordination needed for reaching, lifting, throwing, and many other movements. Understanding the anatomical structures discussed will help you understand why your shoulder dislocated.

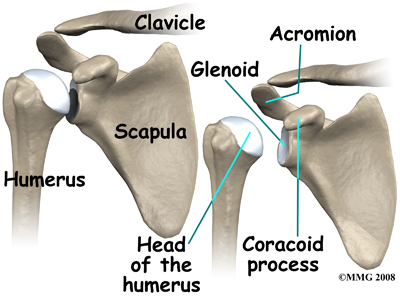

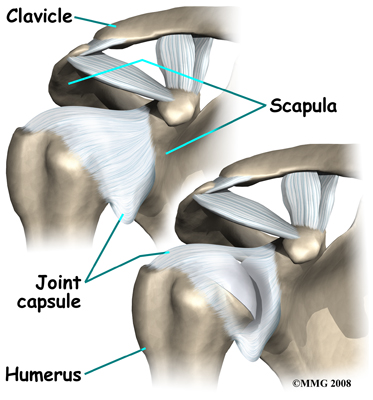

The bones of the shoulder are the humerus (the upper arm bone), the scapula (the shoulder blade), and the clavicle (the collar bone). The roof of the shoulder is formed by a part of the scapula called the acromion.

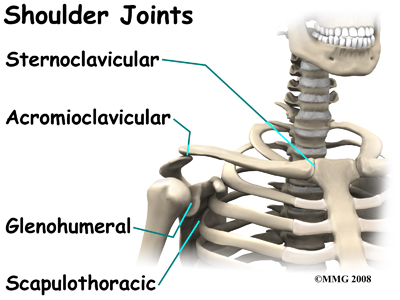

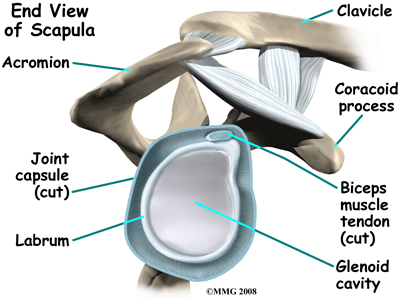

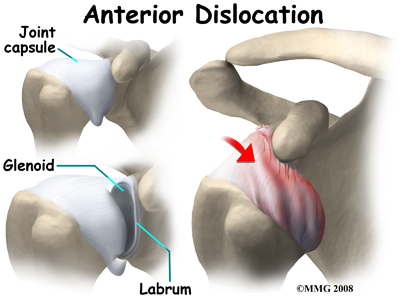

There are actually four joints that make up the shoulder. The main shoulder joint, called the glenohumeral joint, is formed where the ball of the humerus fits into a shallow socket on the scapula. This shallow socket is called the glenoid.

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint is where the clavicle meets the acromion. The sternoclavicular (SC) joint supports the connection of the arms and shoulders to the main skeleton on the front of the chest. The scapulothoracic joint is formed where the shoulder blade glides against the thorax (the rib cage). This joint is especially important because the muscles surrounding the shoulder blade work together to keep the socket lined up during shoulder movements.

Ligaments, Joint Capsule, and Labrum

There are several important ligaments in the shoulder. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect bones to bones. A joint capsule is a watertight sac that surrounds a joint. In the shoulder, the joint capsule is formed by a group of ligaments that connect the humerus to the glenoid. These ligaments are the main source of stability for the shoulder; they help hold the shoulder in place and keep it from dislocating.

There are several important ligaments in the shoulder. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect bones to bones. A joint capsule is a watertight sac that surrounds a joint. In the shoulder, the joint capsule is formed by a group of ligaments that connect the humerus to the glenoid. These ligaments are the main source of stability for the shoulder; they help hold the shoulder in place and keep it from dislocating.

The labrum is a special cartilaginous structure inside the shoulder. It is attached almost completely around the edge of the glenoid. When viewed in cross section, the labrum is wedge-shaped. The shape and the way the labrum is attached create a deeper cup for the glenoid socket and helps to prevent dislocation by creating more stability. This is important because the glenoid socket is so flat and shallow that the ball of the humerus does not fit tightly. This anatomical shape allows great mobility of the shoulder, but unfortunately does not provide much stability, hence the reason it dislocates much easier than some other joints.

The labrum is also where the long biceps tendon from the upper arm attaches to the glenoid. Tendons attach muscles to bones. Muscles move the bones by pulling on the tendons. The biceps tendon runs from the biceps muscle, up the front of the upper arm, to the glenoid. At the very top of the glenoid, the biceps tendon attaches to the bone and actually becomes part of the labrum. This connection can be a source of problems when the biceps tendon is damaged and pulls away from its attachment to the glenoid.

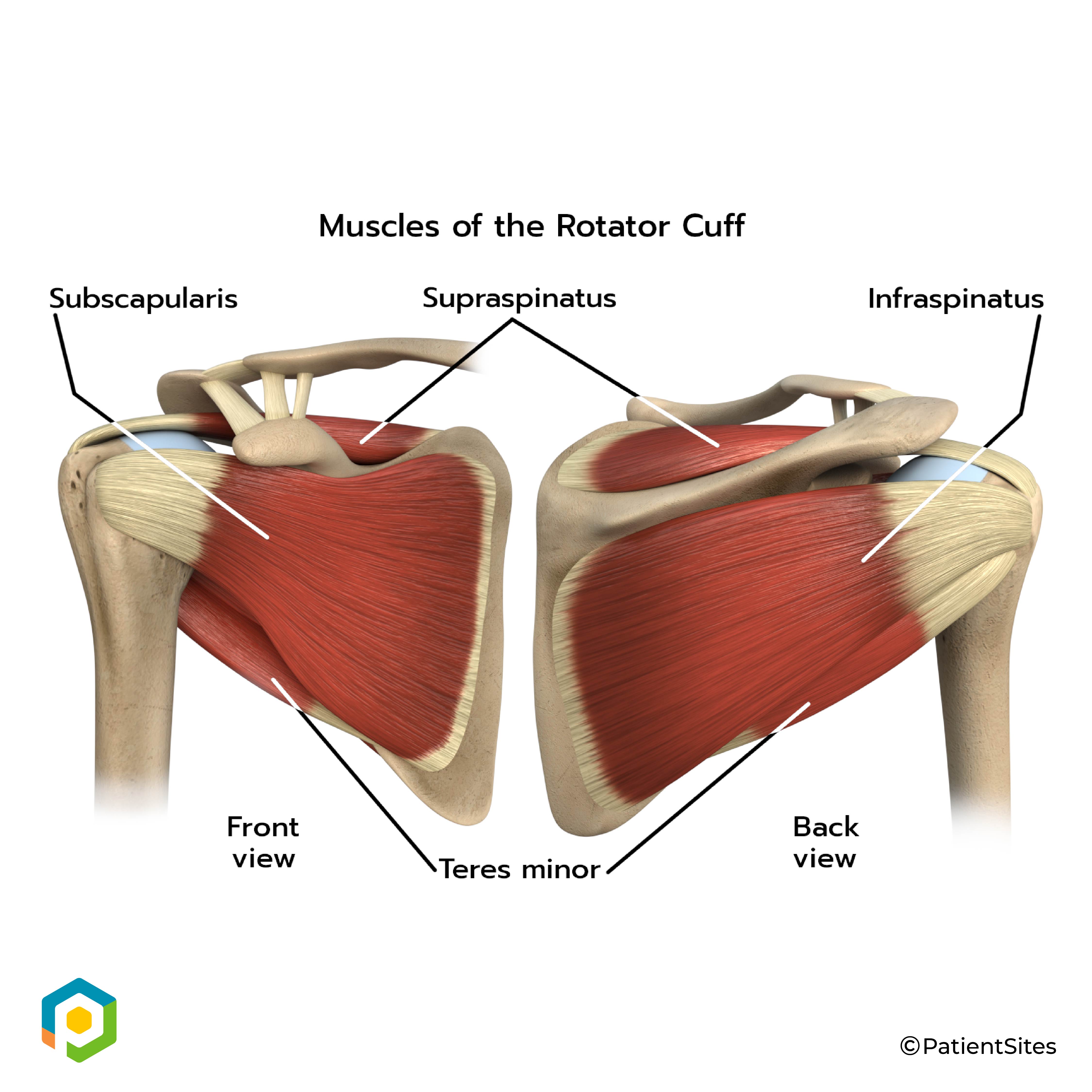

The Rotator Cuff

The tendons of the rotator cuff are the next layer in the shoulder joint. Four rotator cuff tendons connect the deepest layer of muscles to the humerus. This group of muscles attaches from the shoulder blade to the humerus. These muscles help raise the arm from the side and rotate the shoulder in the many directions. They are extremely important muscles to the shoulder and are involved in many day-to-day activities. The rotator cuff muscles and tendons are extremely important in assisting glenohumeral joint stability because they help hold the humeral head in the shallow glenoid socket.

The tendons of the rotator cuff are the next layer in the shoulder joint. Four rotator cuff tendons connect the deepest layer of muscles to the humerus. This group of muscles attaches from the shoulder blade to the humerus. These muscles help raise the arm from the side and rotate the shoulder in the many directions. They are extremely important muscles to the shoulder and are involved in many day-to-day activities. The rotator cuff muscles and tendons are extremely important in assisting glenohumeral joint stability because they help hold the humeral head in the shallow glenoid socket.

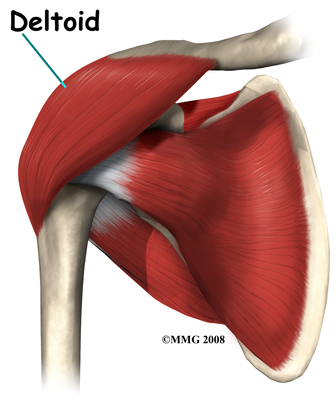

The large deltoid muscle is the outer layer of shoulder muscle. The deltoid is the largest, strongest muscle of the shoulder. The function of the deltoid muscle is to lift the arm further up once the arm is already away from the side of your body.

Related Document: FYZICAL Hazleton's Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Types of Shoulder Dislocations

Anterior Dislocation

With an anterior dislocation, the head of the humerus is driven forward from inside the glenoid cavity to a place under the coracoid process. This type of dislocation is sometimes referred to as a subcoracoid dislocation. The joint capsule is usually avulsed (torn away) from the margin of the glenoid cavity.

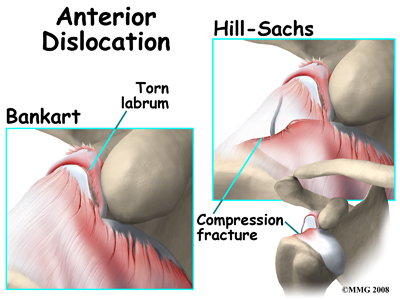

Anterior shoulder dislocation can also be the result of a detached labrum. When both the labrum and the capsule along the anterior margin of the glenoid cavity are avulsed, the injury is called a Bankart lesion. A compression fracture of the humeral head from the force of hitting the hard glenoid during dislocation is called a Hill-Sach's lesion. Seventy-five percent of patients with a Bankart lesion will also have a Hill-Sach's lesion.

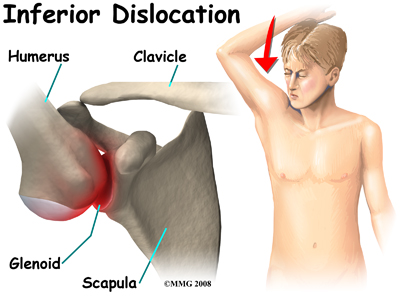

Posterior and Inferior Dislocations

When the shoulder dislocates posteriorly, the head of the humerus moves backward behind the glenoid. An inferior dislocation describes the position of the humeral head down below the glenoid cavity. Posterior and inferior shoulder dislocations only account for about five to 10 per cent of all shoulder dislocations. Most shoulder dislocations are in the anterior direction.